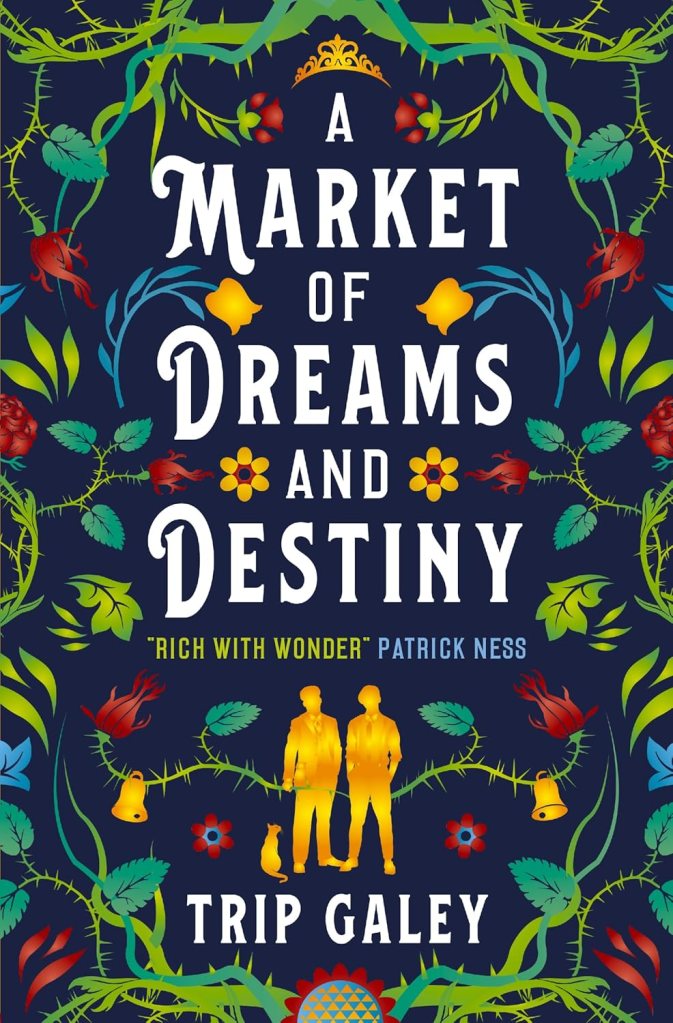

I already know what my first question is going to be. You are both an established author in your own right yet just as A Market of Dreams and Destiny was being published (and you were presumably writing new material) you somehow managed to find time to start your own press. How do you manage to be so productive?

So, the thing with Bona Books is it’s not just me. It’s also my partner Robert, and our friends Chris and Lyam. It’s a lot easier to be productive when you have a team helping you! And the great thing about Bona is that we each have different areas of expertise that we can bring to the table. It takes a lot less energy to do things you’re already skilled at. Chris can edit things in a third the time it takes me, and Robert can do more with social needs in ten minutes than I can do in two hours.

Otherwise, a lot of my productivity is knowing myself and my patterns. I write best in the morning before other people are awake. So the trick becomes ensuring that I make the best use of that time (this does not always happen in the cold, dark times of the year). Similarly, batching and bordering tasks is something I find helpful. For example, doing a chunk of posts for social media once a week, and/or making sure you only check email twice a day (for set periods of time).

What was it that inspired you to start your own press?

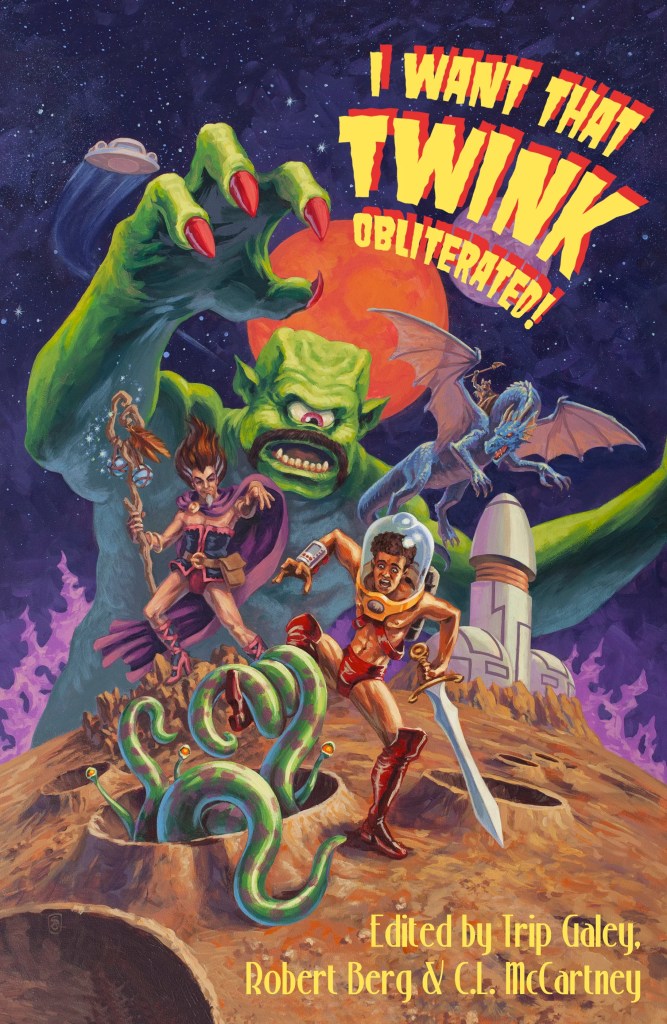

It was literally a joke that began it all, a meme around the kitchen table. Robert and I were living with Chris at the time, and we all worked from home most days. So we’d often have tea breaks and sit together and just chat for a bit before going back to work. Someone sent Robert an “I Want That Twink Obliterated!” meme; we joked that it would be a good SFF anthology title; we did some “fan casting” of the kinds of stories we’d like to see for it; then we went back to work.

Five minutes later though, I saw Chris looming in the doorway out the corner of my eye. He was like, “You know, we could actually do this. We have enough skills between us. So…should we do this? Are we doing this?”

Dear Reader, the reply was obvious. I said “Yeah, I think we’re fucking doing this!”

And we did. And of course it only made sense to then create a small press to put out the book. And then we wanted to do another book, so of course the press began to grow, etc. etc.

But the inspiration was that meme, at that tea break, while we were all living in what we affectionately called “The Writer Flat.”

Bona Books seemed to become successful very quickly with its launch of I Want That Twink Obliterated! I remember a lot of the promotion being very memorable in its inventiveness. Where did you and your team get all of your ideas from?

Being too queer and too online, basically. Haha. Robert was keyed in to which memes were being shared, and I have a knowledge of science fiction and fantasy that runs far deeper than is good for me. Chris is almost as bad as I am, and by later on, in terms of promo, Chris had begun dating Lyam, who has a history in marketing and promotions. So it was a gestalt of everything, really.

Also, it was about having fun. Making the kinds of jokes queer people make with one another, and turning those into memes or adverts or what have you. And I suppose if we’re clearly having fun, it encourages other people to join in! (Read the book. It’s got great stuff inside!)

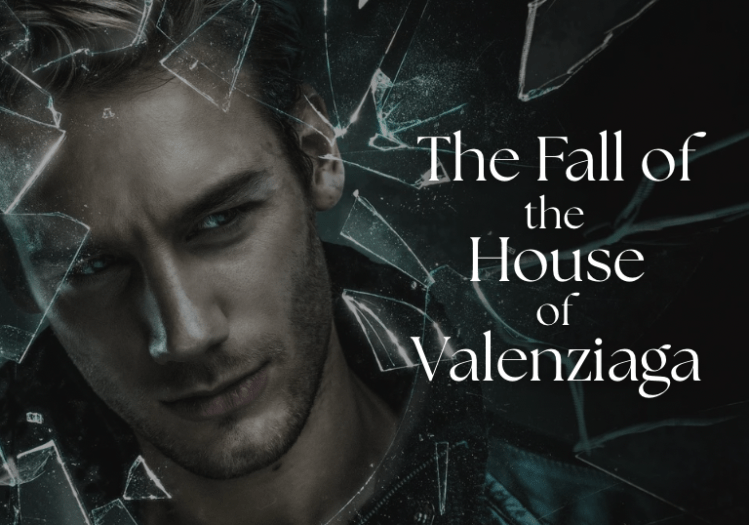

I am very intrigued by The Fall of The House of Valenziaga. Can you tell me some things about it? How does it compare to A Market of Dreams and Destiny?

The Fall of the House of Valenziaga is a story for all those kids with toxic parents who never had the power to fight back against the abuses of power they had to suffer.

It is, to date, the queerest thing I have ever written. The world sprang from the idea that as queer people we routinely have our world(s) destroyed. Being outed in front of queerphobic parents, being disowned, cast out onto the streets, or in the past losing friends and lovers to AIDS—there are so many ways our world(s) can shatter. But we go on. Because we’re beautiful and strong and amazing. Yes, there are scars, edges where things grate or don’t quite fit, but that also makes us us.

Twixt is like that. It’s a city composed of surviving pieces of countless worlds that have been destroyed, each which brings with them a little bit of their sky, a touch of the magic they used to hold, some of their forgotten secrets and disheveled beauty. It is ruled by an amorphous set of Legendary Houses which were inspired by a melange of ball culture and queer culture and fantasy noble houses.

And both the setting and the story are positively rife with references to various aspects of queer culture from throughout history. There are worldmotes (pieces of the city) inspired by Chappell Roan and Jake Shears, Legendary Houses that take inspiration from figures like William Dorsey Swann and Tom of Finland, and more.

But at the core of it, it’s about a broken-hearted boy whose world is shattering around him, and what he does to fight (and possibly destroy) those who abuse the power they hold over him. I suppose in that case, it’s got a strong thematic resonance with A Market of Dreams and Destiny.

What is next for you, both with Bona Books and you as an author?

Bona Books is in the late stages of editing our second anthology, Wrath Month, which is SFF tales of queer rage. We have also begun the process of launching Fantabulosa! which is a quarterly magazine dedicated to queer science fiction and fantasy (prose, poetry, and non-fiction). After that, we have plans for a feminine-focused companion volume to I Want That Twink Obliterated! and a queer winter-solstice-themed anthology. Novellas are something we’d like to branch into, but we don’t yet have the time or the funds to truly dedicate in that direction.

As for me, I have the Kickstarter for The Fall of the House of Valenziaga. And I am in deep in edits on the next Untermarkt book for Titan (it’s not quite a sequel to A Market of Dreams and Destiny, but it’s not not that either). Then I owe my agent a draft of a book I’m working on that plays around with faery, the magical school trope, and kids from abusive homes. And I’m collaborating with an unspecified number of authors on a variety of unnamed novellas.

Honestly, if you want to see more of my work, please support the Kickstarter for Valenziaga! The more money that makes, the more queer fiction I can attempt to usher into the world (because I will have to spend less time looking for non-fiction freelancing)!

What are you currently reading?

I’m currently rereading Roger Zelazny’s Chronicles of Amber. It’s a classic of SFF, but I’m not sure how popular or well known it is these days, unlike Tolkien or Le Guin (who remain perennially read and relevant). It has a lost prince, infinite worlds, the occasional merging of science and sorcery, and lots of intrigue, swordplay, and shenanigans. (I love it.)

Amber (with its infinity of strange worlds, and intense intrigue at the upper levels of society) is very much an influence on The Fall of the House of Valenziaga. Of course, Amber was also written in the late 70s by a cishet white dude, so it does fall prey to some of the expected stereotypes. There is, however, the occasional strong, empowered female character, and the voice and writing style make for an easy, enjoyable read with moments of true poetic beauty.

It is, so far as I have found, the best example of science-fantasy in fiction. That’s not to say I won’t eventually find something that meets or exceeds it—my TBR does have some modern examples I am very excited to get to. Someday. If I ever have enough free time again…

And finally, would you like to give a shout-out for three books which you feel more people should read, and tell us why?

Happily!

Kid Wolf and Kraken Boy by Sam J Miller. This urban fantasy novella is set in the 1920s, features gay Jewish boxers, a lesbian mob boss, tattoo magic, and is one of the best-crafted (and just amazingly fun) reads I can think of. It deserves so many more eyes on it.

The Shadow Glass by Josh Winning. This is very much a love letter to Jim Henson and The Dark Crystal. The son of a famous puppeteer and movie maker discovers that his estranged father’s most famous work might be a bit more…real…than anyone suspected. Def check it out.

The Fell of Dark by Caleb Roehrig. Imagine Buffy the Vampire Slayer, but gay male teen. It’s a really fun, dark, funny book, and it has the sexiest not-sex scene I have ever encountered. It’s not a threesome, but it’s also not not a threesome? Anyway, I highly recommend it.

Please click here if you want to find out more about Trip Galey, follow him on social media or find out more about his books and Bona Books!